On Friday, May 13, 1921, The Springer Times published their Springer High School Edition. It reads much like school newspapers everywhere, featuring articles on school sports, activities, and writings by the students. At the time, Joseph Cunningham was 16 years old and in the Sophomore class, which appears to have had just 12 students: 6 boys and 6 girls. Consequently, the newspaper features a lot more personal detail about individual students than I would have found in my high school newspaper.

In the clipping, Joe is listed as the Class President, and we are treated to a little bit of doggerel called The Sophomores, which devotes a verse to each member of the class and 4 girls who had left the class. I have not included the whole poem as it gets a little tedious. However, it does tell us that Joe is the second tallest boy in the class, next in stature only to Carl Shirley, and that:

In English he’s quite stubborn

But elsewhere he’s a lamb.

The paper also features a short story by my father entitled The Hunch, which I have included in the Stories section of this site. The first verse of the The Sophomores may contain an oblique reference to this story. This story, which is the earliest of my father’s writings that I know of, is interesting, not because it is a great work of literature, but because of the insight it gives into what the 16 year old Joseph Cunningham cared about.

Briefly, the story is about a young man, William Farley, Jr., just graduated from college with a degree in geology, who has been sent to New Mexico by his father in Wyoming to make a geological survey of some land had been offered for sale to determine whether it would be worthwhile to purchase it and drill for oil. However, in college, William Jr. “really didn’t attend to business and studies enough to become an expert geologist.” So, even though he really doesn’t have a clue as to whether or not the land might contain oil, he decides to play a “hunch” and recommend to his father that he buy the land and drill for oil. If he strikes oil, he will split the profits evenly with his father and be able to marry. Several months later, we find young William leading a drilling crew on the land, not striking oil, and facing “labor difficulties” when he is unable to pay his crew when his father cuts off his line of credit. The plot does not really get resolved, it just trails off into an epiphany of manliness.

What I find interesting about the story is not so much the plot, which I have rather cavalierly dismissed, but the descriptions.

The story opens with a rather florid description of the young man enjoying the beauty of the evening in the New Mexico countryside. I have no doubt that Joe was writing about what he knew here. He was a teen, raised on a ranch near Springer, who was describing the clouds, the golden sunsets, the views of the mountains, and the evening coolness after a hot day that he knew and loved. We are also introduced to young William’s longing to marry “the lady of his heart’s desire.” Certainly this is not an uncommon preoccupation for a16 year old.

A little later, we are introduced to William’s only friend nearby, an Airedale dog named “Bummer”. I’m sure Bummer is based on an Airedale named “Yellow Boy” that my father had when he was a boy and that he told me about many, many times. The stories of Yellow Boy that he told when I was young were of adventures, mainly Yellow Boy chasing badgers, skunks, or porcupines, with unfortunate and dramatic consequences. His descriptions of Bummer I’m sure are descriptions of Yellow Boy that he left out of his stories: how they had met, how he had a place in his heart, what he felt when he looked into his eyes, and how they understood each other. I don’t recall him ever telling me these things about Yellow Boy directly, although he may have, but the fact that he told me so many stories about him over forty years later is a pretty good indication that he felt he had a very special relationship with his dog.

When I was fairly young, I received a beautiful slip-cased, hardcover copy of Anna Sewell‘s Black Beauty, which I loved. I probably first struggled through it in the second-grade. I distinctly remember reading it for the second time when I was in the third grade. It deeply influenced my attitude towards animals then, objectifying them less, anthropomorphizing them more, but taking the lesson that they were thinking feeling beings who should be respected and treated with kindness. I embarked on reading a whole series of animal books, as is common for kids of that age: Walter Farley‘s Black Stallion books, Eric Knight‘s Lassie Come-Home, and many more. My father, undoubted noticing the trend, and possibly thinking of his relationship with Yellow Boy, bought me a copy of Margaret Marshall Saunders‘s novel Beautiful Joe as a birthday or Christmas gift sometime around when I was in the fourth grade. He might have chosen it thinking back to his relationship with Yellow Boy because Beautiful Joe was an Airedale-type dog, or simply because he was a dog. However, I have to confess that I never read the novel, even though I thought it was a wonderful gift and felt guilty about not reading it for years. The simple reason is that because Beautiful Joe is described as having been abused nearly to the point of death and having his ears and tail cut off, it simply seemed too painful to read. However, it still remains one of those books that I want to read. I’m fairly certain that I will find my preconceptions are probably wrong and I will find it much different than my 10 year old self imagined.

One of the other interesting points that I noted about The Hunch was related to a remark Joe once made to me when we were on a train leaving Los Angeles, headed north to visit his brother Burris’s family in Berkeley. We were passing through some rolling hills when he said that he was sure there was oil beneath those hills because of their dome shapes. He seemed curiously insistent on the point. I tended to disbelieve him about this point then, as I do now, for the simple reason that that area has been so extensively explored and drilled for oil for many decades that it seemed almost certain that the possibility must have already been thoroughly explored by many others. The story left me wondering whether there was some relationship between it and his insistence that there was oil beneath those hills north of Los Angeles.

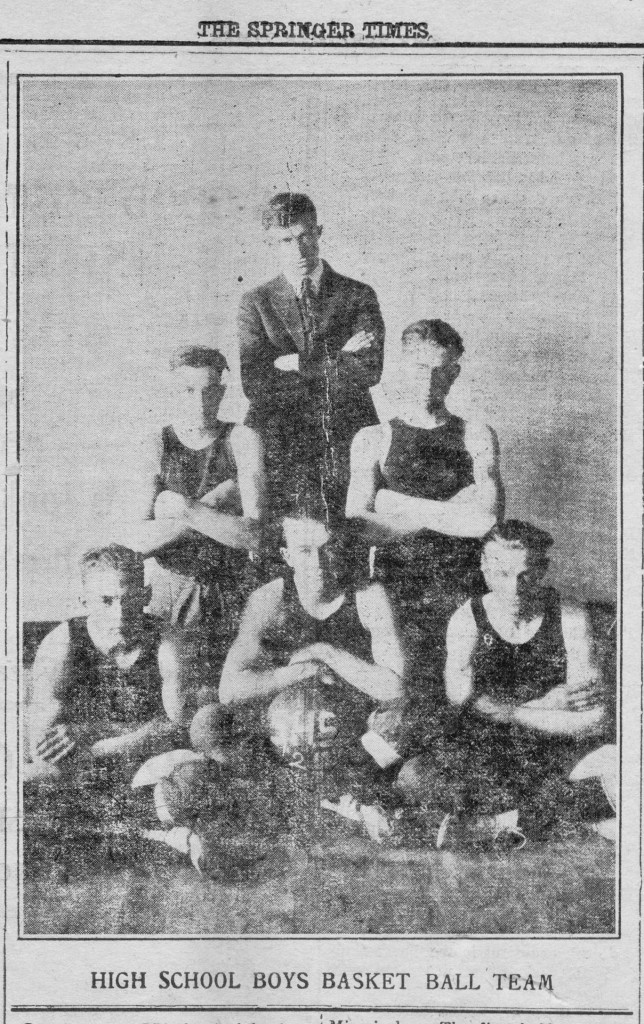

Another highlight of this issue of The Springer Times is that it apparently contains the earliest photograph that I have of my father. The irony is that he is in a group shot and I am not sure which one is him. The Springer High School Basket Ball team consisted of Raymond Tindall, forward (Capt.); Paul Bruce, forward; Lawrence Abreu, center; Joe Cunningham, guard; Roy Hunter, guard. Substitutes, Carl Shirley and Evans Milton. I guessing that my father is at the middle-left or lower-right, but I really don’t know.

I met Larry Abreu several times when I was young. He lived in Los Angeles and my father would see him from time to time. For the longest time I never understood just who he was or what his relationship to my father was. I think I was in high school before Joe finally explained to me that he had gone to high school with Larry Abreu. But until going through this newspaper I did not really understand what that must have meant to him. There were 410 people in my (half-year) high school class. I barely knew most of them. There were 12 people in my father’s full-year sophomore class. Larry Abreu was a year or two ahead of my father in high school, but he was a lifelong friend that grew up very close to him. Larry Abreu died sometime in the 1960s, several years before my father. He did not speak of it much, but I’m sure Joe took his death hard as it was a reminder of his own mortality.

One Response to The Springer Times, May 13, 1921